Atlas Under the Dermis

Ash and Lark run an after-hours tattoo studio where star-charts double as keys. Rowan arrives with one demand: a constellation inked at 02:17. But the printout carries a missing star, the radio static thickens, and the stencil begins to shift — turning a clean procedure into a vigil that answers back.

The Hour Kept

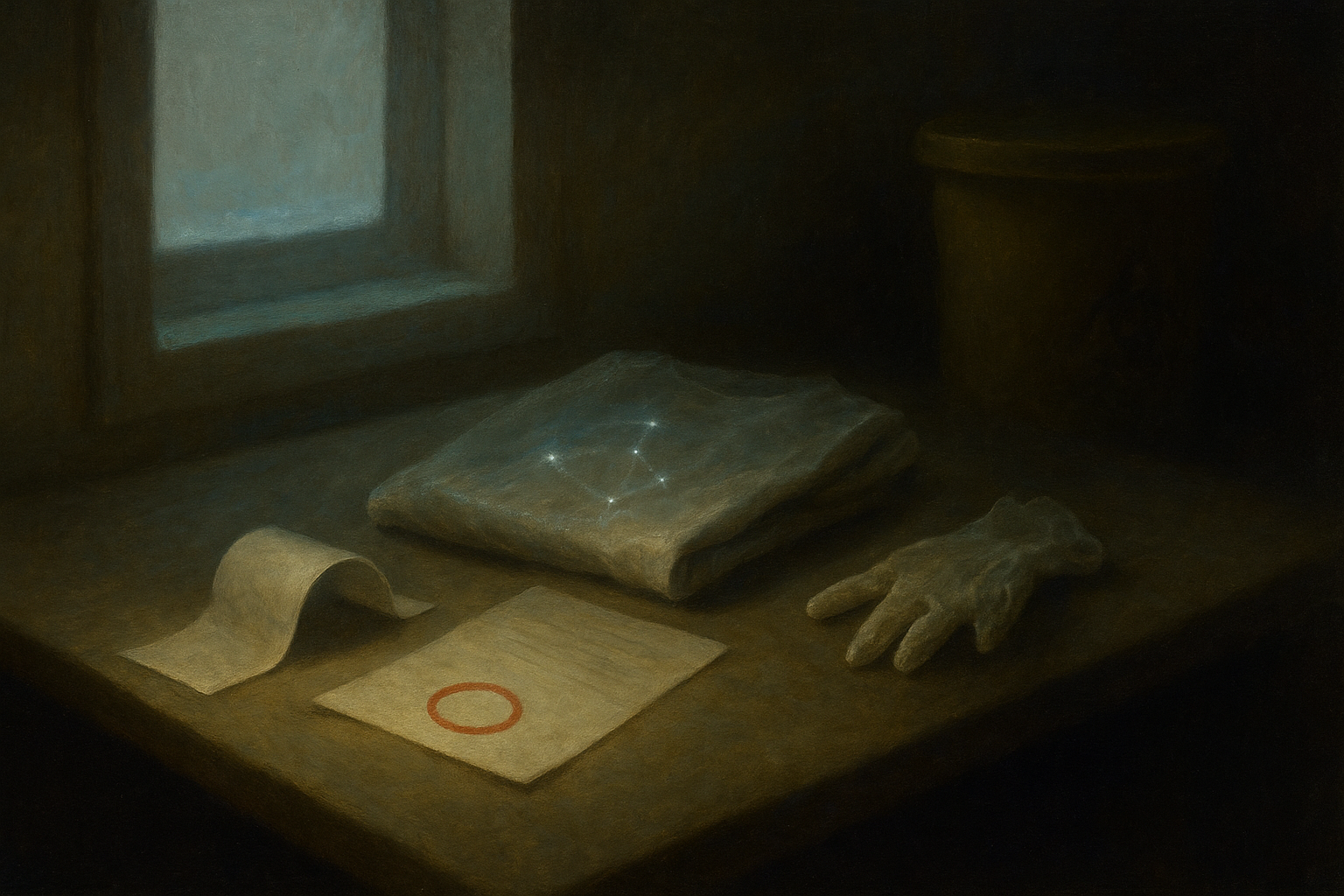

The ephemeris pages curl at the corners under the antiseptic glare, as if paper can recoil from precision. Stainless steel reflects them back — thin white sheets with black dots and coordinate strings, a sky reduced to bookkeeping — and in the middle of the top page, circled hard enough to bruise the fibers, sits the minute: 02:17.

I circle it again anyway, red ink tracking the same loop my mind has been walking for months. The circle is supposed to mean contained. The circle is supposed to mean kept.

On the counter, the thermal printer coughs out another strip — calibration report, timestamped, clipped. UV sterilizers glow in their sealed cabinets like votive candles for a faith that cannot bear smoke. The room smells like isopropyl and glove powder and the faint metal sweetness of machine oil, the three-note chord of our after-hours chapel.

Lark stands in the doorway to the back room without entering. They don’t crowd a setup. They don’t hurry. Their stillness is its own kind of pressure.

“You’ve got the alignment circled,” they say, as if it’s a weather forecast. As if it’s not a feast day.

“I have it circled,” I answer, voice in my professional register — the one that keeps my throat from doing anything foolish. I keep my eyes on the cartridge pack. Sealed. Lot number. Expiration. I read it like a prayer I don’t admit is prayer.

Lark comes closer. Their hands are already gloved; their hair is netted back; their face is clean in the same way surgical lamps are clean — nothing hidden, nothing softened. “Run the motor at twelve volts. Listen for the hum to settle. Don’t compensate with speed; compensate with breath.” Then, gentler, “You slept?”

“I rested.” A lie, but a small one, the kind we all use to keep the night from suspecting us.

The coil machine is old enough to have its own superstition, but we use rotary pens now: cartridge-based, disposable, precise. I snap one into the grip with a click that feels like a latch on a coffin. When I tap the foot pedal, the needle starts its tight, insectile oscillation. The hum is a metronome. The hum is bees. The hum is a chant you don’t have to believe in for it to take up residence behind your teeth.

It steadies. I let my shoulders drop one fraction of an inch, and in that small surrender my body offers up a memory it shouldn’t have, a single sentence spiraling up through my sternum:

02:17: the door, the cold air, the sound of my own name from somewhere I wasn’t.

I swallow. The taste of antiseptic goes sharp.

Lark slides a small vial across the steel toward me. The glass is thick, medical-grade; the cap is sealed in tamper film. Inside, the ink has a slow internal gleam, like plankton trapped in a bottle. Bioluminescent. Legal for medical marking. Not legal for what we use it for.

“Only if they ask,” Lark says, as if they can hear my pulse editing my thoughts. “Only with explicit consent. You know the protocol.”

“I know.” I set the vial beside the other inks, away from the overhead light so it can’t show off.

The shop is quiet because it’s supposed to be closed. The front signage is dark. The street outside is a smear of wet neon on asphalt. The comms blackout started at dusk — satellite drift or regime interference or a storm nobody owns. Our network’s down. No streaming. No calls. No weather. Just the old radio on the shelf, its antenna angled like a bent finger pointing nowhere, and its mouth full of static.

Static is the closest thing we have to choir.

Lark turns the lock on the back room door — not to trap us, they would say, but to seal the rite. “Bottle,” they called it once, half-smiling. “If you can’t endure a room, you can’t endure what the room is for.”

“What if the client—”

“They’ll come,” Lark says, and their voice makes it feel inevitable. “They always come. Grief is punctual when it thinks it can be paid.”

I wipe down the chair in the front room until the vinyl squeaks. I lay out barrier film. I set caps in a neat row. I fold the transfer paper as if it’s fragile skin. I align everything. I align everything because alignment is what we sell: the promise that if the sky can be made legible, then what it took might be made in return.

On the wall above the consent counter, the analog clock ticks. It’s honest. It doesn’t care about satellites. It doesn’t care about gods. It doesn’t care about me. Its hands keep moving through all the minutes that have ever failed anyone.

Midnight. 00:00. I make the first note in the logbook: Vigil session initiated.

Underneath, in smaller letters I do not mean to write like a confession: Do not miss the minute.

Someone Steps Inside

The bell over the front door is disabled after-hours, but I still hear it when the client arrives — an absence that rings anyway. The camera feed on the monitor shows them outside for a second before they’re inside, as if the street exhales them into the shop. They stand in the entryway and let their eyes adjust to our sterile white light, shoulders stiff, hands empty in that way people hold themselves when they are trying not to spill.

“Rowan?” I ask, matching the file. Coded appointment. Cash deposit. A single line in the intake form: Vigil receiver. Alignment 02:17.

They nod. Their hair is damp with rain. Their face has the drawn look of someone who has been awake too long or asleep too hard. They look at the closed neon sign as if it’s a lie. Then they look at me as if I’m supposed to correct the universe’s timing.

“You’re Ash,” they say. Not a question. My name lands like a coin on metal.

“I’m Ash.” I gesture toward the consent counter. “We’ll go through paperwork first. Then placement. Then we’ll decide ink.” My voice stays clipped, clean. Inside, my mind runs little loops of contingency: If they’re high. If they faint. If they try to move. If they—

Rowan steps up to the counter and lays down a folded stack of ephemeris printouts. The pages are creased and annotated in thin black pen — marks like marginalia in a prayer book. There are timestamps written in the corners, circled, underlined, circled again.

“02:17,” Rowan says. “You have it?”

“I have it,” I answer, and I hate the way the words echo. “We work with the clock in the room. We can’t guarantee satellite sync during a blackout.”

Rowan’s mouth tightens. “It’s not the satellites that matter. It’s the alignment.”

Lark appears from the back room with a towel over their shoulder, as if they’ve just come from baptizing something. “You’re here,” they say to Rowan, not welcoming, not unkind. Simply acknowledging the fact that inevitability has a face. “You understand what this is.”

Rowan looks at Lark the way people look at authority when they don’t believe in it but need it anyway. “I understand you do vigil work.”

“We do tattoo work,” Lark says. “Vigil is a word clients bring to make their desire sound holy.”

Rowan flinches, then steadies. “Call it whatever you want. I need it done at the minute.”

I slide the consent forms forward. “This is a standard agreement plus additional clauses for timed work. You can stop at any point. You can take breaks. You can withdraw consent and we stop. You can ask to see the stencil before we transfer. You can ask questions. You can refuse anything.”

Rowan picks up the pen. Their hand shakes only once.

They initial each line: pain tolerance; aftercare; infection risk; consent to biometric imprinting of the design — standard legal language that pretends tattoos aren’t already a ledger. When they get to the clause about non-guarantee of “signal reception,” their pen pauses.

“This,” Rowan says, tapping the paper, “is why I’m here.”

“This,” I say, tapping back, “is why we don’t promise what we can’t ethically promise.”

Rowan’s laugh is a short burst, almost static. “Ethics. I’m not asking you to raise the dead. I’m asking you to do what your system does.”

Lark’s gaze stays level. “Our system prints ephemerides from a satellite feed. It does not deliver messages from missing people. If you heard that, you heard it from someone who needed the story to be true.”

“I heard it from someone who has the mark,” Rowan says, and there is a tremor in their voice that is not fear but insistence. “They said the ink… glowed when it was time. They said the radio went strange. They said—” They swallow. The next word catches like a fishhook. “They said a name came through.”

Name. Noise. The small holy shiver of it.

My hands, in gloves, feel too clean.

“What’s the placement?” I ask, professional, because if I don’t ask, my mouth will ask something worse.

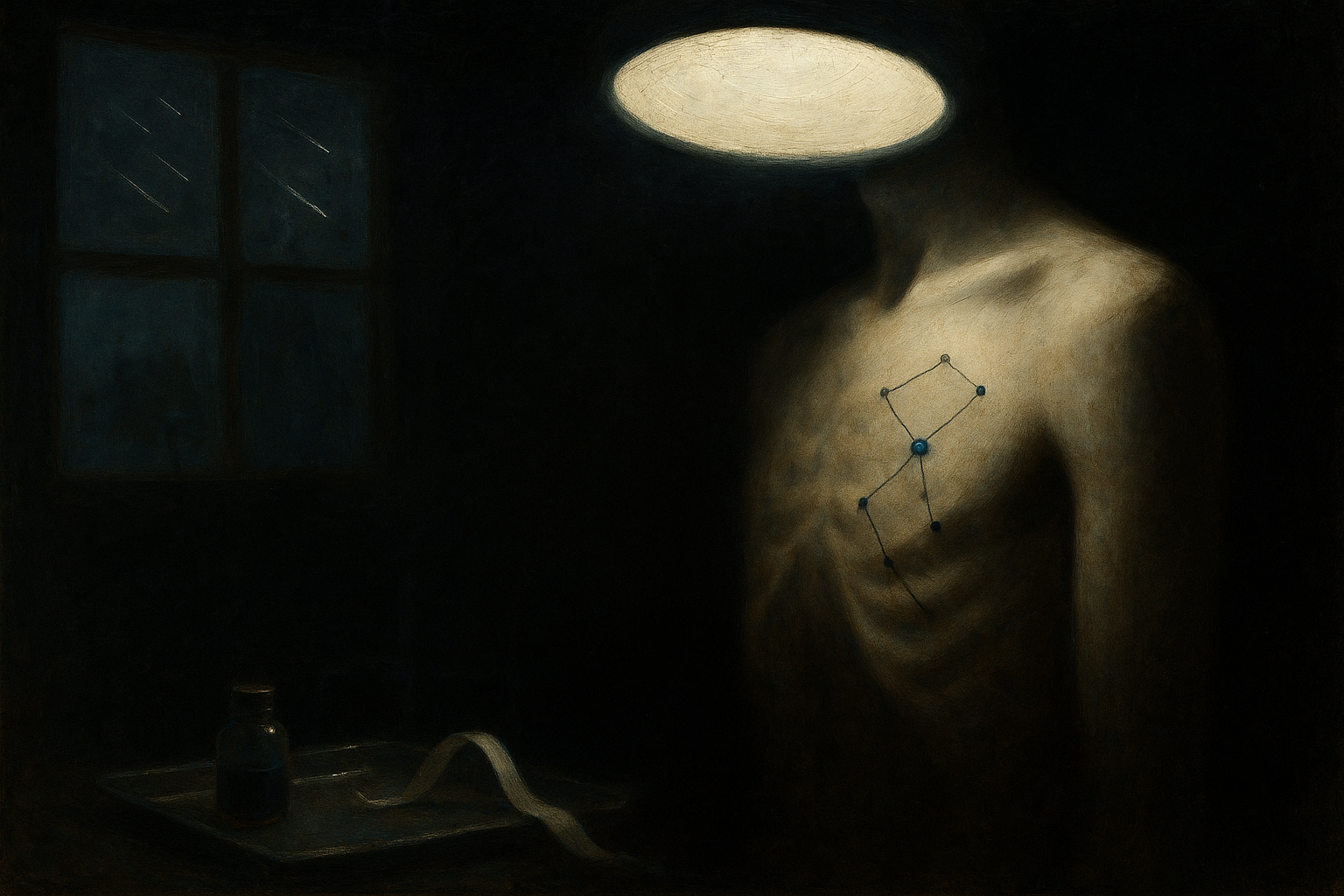

Rowan pulls their jacket off and turns slightly, showing the left side of their torso. Not bare yet — just the implication. “Here. Ribcage. Heart-line.” Then, quieter, “It has to be close enough to hear.”

“Painful spot,” I say.

“I’m not numb-ing,” Rowan replies, as if they’ve rehearsed this refusal in the mirror. “I need to feel it.”

“Feeling pain doesn’t make it truer,” I say before I can stop myself.

Rowan’s eyes snap to mine. “Not truer,” they say. “Present.”

Lark touches the consent form with one gloved finger. “We don’t do this if it’s coercion,” they say, and their voice has teeth. “If you’re punishing yourself, go elsewhere. If you’re using Ash as a tool, go elsewhere. If you cannot keep your consent intact when the needle hits, go elsewhere.”

Rowan’s jaw works. “I’m not punishing myself,” they say. “I’m—” The word collapses. They try again. “I’m keeping watch.”

Gethsemane blooms behind my eyes like a bruise. Could you not watch with me one hour?

I keep my face neutral. “We’ll do the stencil,” I say. “You’ll see it. You’ll confirm. Then we’ll proceed. And I’ll check in with you throughout.”

Rowan nods once. “Do it,” they say, and the command is too familiar, too close to another night I won’t let my mouth name.

I gather their papers. I move toward the back room to feed the printer, and as I pass the analog clock, its minute hand ticks over like a small blade: 00:14. Plenty of time. Too much time.

Time is a corridor. Time is a locked room. Time is a vigil you can fail by stepping out for one second.

A Star Refuses Its Place

The ephemeris software is old and temperamental, stitched together from astronomy APIs and encrypted overlays that Lark refuses to let me fully see. It pulls the client’s birth data — Rowan’s date, place, exact time — and maps it against the current sky, calculating angular distances, plotting coordinates, printing out the dot-field we’ll translate into flesh.

Usually, it’s straightforward. Usually, the printer’s heat head burns clean black points into paper. Usually, the stencil is an icon: sharp dots, precise lines. A chart you could trust.

Tonight, the first printout comes out with a smear through the upper left quadrant, as if the sky has been dragged by a thumb.

I stare. I reprint. The second printout has the same smear, but the smear is in a different place.

“That’s interference,” I say to nobody.

The radio on the shelf hisses, low and constant.

I reprint again, adding a manual checksum. The software flags DATA INCONSISTENT in a tiny gray box, apologetic. Then, in the middle of the dot-field, there is a blank spot where a star should be — an absence so deliberate it reads like punctuation.

A missing star.

I touch the paper with the tip of a gloved finger, as if I can feel the blankness. My pulse taps my wrist: too fast. I look at the timestamp on the printout: 00:22. I look at the circled 02:17 on the earlier page. The gap between them feels like a descent.

Lark leans over my shoulder, eyes scanning. “Print again,” they say softly, and the softness makes it worse. “Don’t argue with it yet.”

“It’s wrong,” I say.

“The sky is always wrong,” Lark says. “We’re the ones who pretend it’s stable.”

I want to tell them the system never does this. I want to tell them my hands are steady enough to ink through an earthquake if the data holds. I want to tell them that if it holds, everything holds. I want to tell them what happened at 02:17 on another night when I stepped out and the world made a decision without me.

Instead I say, “We can’t transfer a corrupted stencil.”

“We can transfer what we have,” Lark says. “We can watch what it does.”

“That’s—” The word I want is reckless, but the word that rises is faith, and I bite it back. “That’s not protocol.”

Lark’s gaze meets mine. “Vigil is protocol,” they say. “Vigil is staying. Vigil is not leaving when the room asks you to leave.” Then, as if they can smell the way my body goes cold at that last phrase, they add, “You’re not alone in it.”

I look at the locked drawers under the counter — metal, key-coded, each labeled with a number I’ve never been allowed to ask about. In my peripheral vision, I see the scarred regulars in memory: people who came in with their sleeves rolled up, their wrists already dotted with faint luminous constellations, their eyes refusing to meet the cameras outside. Bodies as ledgers. Star-charts as keys. A network implied like a shadow behind the wall.

Lark doesn’t mention it. They never do. They teach in absences.

I take the cleanest printout — the one with the missing star like a held breath — and carry it to the front room, where Rowan sits in the chair like it’s an altar they’re willing to bleed on.

“Okay,” I say. “Stencil preview.”

I tape the printout to the mirror behind the chair so Rowan can see it right-side-up. In the reflection, our faces float over the dot-field like ghosts. Rowan’s eyes fix on the blank spot instantly.

“That,” they say, pointing. “That’s it. That’s where it goes.”

“That’s where it doesn’t go,” I correct, too sharply. Then I soften. “That’s missing data. It might change when the feed stabilizes.”

“It’s missing because he’s missing,” Rowan says, and the sentence is so simple it almost convinces me.

“He,” I repeat, careful. “The person you’re here for.”

Rowan’s throat works. “Elias,” they say, and I try not to flinch at the biblical weight of it. “My brother. They took him at a checkpoint last winter. There’s no record. No detention. No body. Just… absence.” They tap the blank spot again, as if they can force the paper to admit something. “He was supposed to come home. He was supposed to—” Their voice breaks, then reforms into steel. “This is how I find him.”

I keep my tone clinical. “A tattoo won’t override a regime.”

“It’s not the tattoo,” Rowan says. “It’s the minute. It’s the alignment. It’s the way your ink catches something the scanners don’t.”

The scanners. The unspoken. The off-page apparatus pressing in from outside, even through blackout.

“Are you consenting to the design as shown,” I ask, because my job is to anchor us in what can be said.

Rowan looks at me in the mirror. “Yes,” they say. “And I’m consenting to you doing it at 02:17. And I’m consenting to whatever you have to do to make it… receive.”

“Define receive,” I say.

Rowan’s eyes shine, not with tears yet but with the pressure behind them. “Let him speak,” they whisper. “Through the static. Through the needle. I don’t care. Just—” Their breath catches. “Just don’t let it be nothing.”

I want to say nothing is sometimes the only honest thing. I want to say I have watched nothing swallow a room. I want to say 02:17 is a mouth that doesn’t close.

Instead I ask, “Do you want numbing?”

“No.”

“Do you want to stop?”

“No.”

I nod. I can respect a clear no. I can respect a yes that knows what it costs. Consent is fragile, and tonight it feels like glass in my hand.

I bring out the transfer paper. I clean Rowan’s skin with antiseptic wipe until it squeaks under my palm. Their ribs lift and fall under my gloves. I shave a small strip of hair. The body under my hands is warm, living, insistent. Flesh is always more real than a map.

When I press the stencil to their side, the transfer paper is cool and damp, a skin for the skin. I smooth it down, aligning it to bone landmarks, counting breaths the way Lark taught me: inhale, exhale, stay. The hum of the machine in the other room seems to reach through the wall like a heartbeat.

“Tell me if you want me to stop,” I say into Rowan’s hair.

“I won’t,” Rowan answers, voice muffled against the headrest. “Don’t you stop.”

There it is again. The command.

I peel the transfer paper back.

At first, the stencil looks perfect: crisp purple dots, fine lines connecting them in a geometry that makes the ribcage look like a drafting table. Constellation-lines like sutures, precise, tidy.

Then I see it.

The missing star is not missing.

It’s there now — faint, a small dot off to the side, as if it couldn’t decide where to be. A dot that wasn’t on the printout. A dot that shouldn’t exist.

Rowan twists to look in the mirror, and their breath stops when they see it. “It moved,” they say, reverent and terrified.

“It… appeared,” I correct, but my voice doesn’t believe itself.

Lark, behind us, says nothing. The radio crackles — a brief spike of static like a throat clearing.

I wipe my gloved finger over the dot. It doesn’t smear. It holds.

The data is wrong becomes the sky is answering, and the shift is not a thought; it is a pressure behind my eyes, a tilt in the room’s axis.

02:17: the sound of a chair scraping, my hands empty, someone saying “Ash” as if it’s a warning.

I blink hard. The dot remains.

“Okay,” I say, and my professional tone is a thin sheet over something deeper. “We proceed.”

The Long Nearness

The hours between midnight and the alignment minute stretch like a rosary you don’t want to finish. Each bead is a procedure: glove change, ink cap, needle swap, wipe, stretch skin, lay line. Each bead is a choice to remain.

Rowan’s skin takes the ink cleanly. Their pain is visible in the way their toes curl, the way their fingers grip the chair arm, but they don’t flinch away. They breathe in short controlled bursts through their nose. Their eyes stay open, fixed on the mirror as if watching their own body become a page could summon an outcome.

The machine hum fills the room. Bees. Chant. Metronome. It settles into my bones until my hands move on instinct, a skill older than my thoughts: stretch, breathe, ink, wipe. The constellation-lines go down like sutures, fine and deliberate, stitching a sky to a body.

Every few minutes I check in.

“How’s your pain?” I ask.

“Here,” Rowan says, tapping the air near the heart-line. “Good. Keep going.”

“Do you want a break?”

“No.”

“Do you want to stop?”

Rowan looks at me in the mirror with eyes too bright. “Do you?”

The question is a hook. I keep my face still. “No,” I say, and it’s true in a way that frightens me.

Lark sits at the counter with the radio turned low, as if listening to a sleeping animal. The static shifts sometimes, rises and falls, a tide of interference. Every time it spikes, the hairs on my arms lift under my sleeves.

At 01:11, the overhead lights flicker once. Rowan notices. “They’re watching,” they whisper.

“No,” I say automatically, because denial is another kind of protocol.

Lark’s voice drifts from the counter. “Power grid’s unstable,” they say. “The city’s old. Don’t mythologize it.”

Rowan laughs without humor. “You mythologize everything,” they say.

Lark doesn’t answer. The radio hisses.

At 01:43, when I reach the quadrant of the stencil where the missing star’s dot sits, the dot is no longer where it was. It has migrated a centimeter toward Rowan’s sternum, like a small guilt crawling toward the heart.

I freeze. My hand hovers above skin with the needle poised, humming. The moment dilates. The hum becomes loud. The room becomes too bright.

Rowan’s voice is tight. “What?”

“The dot moved,” I say, and the words feel like profanity in a clinical space.

Rowan cranes their neck, eyes searching the mirror. They see it. Their breath catches. “That’s him,” they whisper. “That’s him trying to—”

“Or it’s ink bleed,” I say, reaching for a rational explanation like a handhold on a slick wall. “Transfer can—”

“It’s moving toward the heart,” Rowan says, and their voice is not triumphant. It’s pleading. “Let it.”

I glance at Lark. Their eyes meet mine with a stillness that feels like a hand on my shoulder.

“Watch,” Lark says softly. “Don’t chase.”

My misbelief rises like a reflex: If I can map it precisely enough, I can keep it from leaving. If I can pin the dot, I can fix the sky. If I can fix the sky, I can fix what happened at 02:17 the last time.

I wipe the area gently with antiseptic. The dot holds, then — so slow it could be my imagination — slides another millimeter.

My stomach turns. The horror is not gore. The horror is legibility. The horror is being shown that control is a costume.

Rowan’s voice is hoarse. “Don’t fall asleep,” they say suddenly, and the words hit my chest like a shove.

“I’m awake,” I snap, too fast.

Rowan’s eyes in the mirror are fierce. “You don’t look awake,” they say. “You look like someone who has stepped out before.”

The air goes cold. The hum keeps chanting.

Lark’s gaze drops to my hands. “Break,” they say. “Coffee. Radio check. Ash — breathe.”

Rowan shakes their head. “No breaks. We’ll miss it.”

“We won’t miss it,” Lark says, and their certainty is frightening because it isn’t rooted in math. “Break now. Consent includes rest. Vigil includes rest. The hour before the minute is the most dangerous.”

Rowan’s jaw clenches, then loosens. “Fine,” they say. “Five minutes. Not more.”

I withdraw the needle. I cap it. I wipe Rowan’s skin and lay a clean wrap over the fresh lines. The constellation glows faintly under the film — not from the ink yet, but from the way the overhead light catches the wetness, making it look like stigmata for a secular age.

“Stay seated,” I tell Rowan, and the instruction carries more weight than it should.

I walk to the back counter on legs that feel slightly wrong, as if the floor has shifted by a degree.

The coffee in the break room is stale and burnt. I pour it anyway. I drink it too fast. Heat hits my empty stomach like punishment.

Lark turns the radio dial with slow precision. The static thickens, thins, thickens again. Underneath, for one heartbeat, there is a tone — thin, high, almost musical — then it’s gone.

“You hear that?” Rowan calls from the chair, voice strained.

“I heard something,” I admit.

Rowan’s laugh comes out like a sob. “That’s him,” they say. “That’s him in there.”

Lark’s eyes flick to me. “Don’t confirm,” they murmur. “Don’t deny. Witness.”

Witness. Watcher at the threshold. A word that makes my throat ache with memories of church I thought I’d outgrown.

Rowan’s gaze stays on me. “You’ve done this before,” they say, softer now. “Vigil. You’ve… received.”

I keep my face blank. “We’ve done timed work,” I say.

Rowan’s fingers pick at the chair’s vinyl. “Someone told me you failed once,” they say, and the cruelty of it is unintentional. It’s just grief looking for structure. “They said you left the room.”

My mouth goes dry. The clock on the wall ticks. The radio hisses. In the silence between one tick and the next, my body offers another micro-flash, one sentence that I cannot stop:

02:17: the smell of rain on hot asphalt, my gloves still on, my phone in my hand, the word “missing” on the screen.

I set the coffee cup down so hard it rattles.

Rowan’s eyes widen, realizing they hit something alive. “I’m sorry,” they say quickly, and for a second the weaponized grief becomes simply grief. “I didn’t mean— I just— I can’t—”

“I know,” I say, and the words surprise me by being true.

Rowan’s voice drops. “If you fall asleep,” they whisper, “if you step out… he’ll go farther. Don’t you understand? He’s already—” They stop, because the rest of the sentence is a cliff.

My professional tone cracks at the edge. “It’s not that,” I say. “It’s not… a lever you can pull.”

“What is it then?” Rowan demands, and there’s the hardness again, the need to turn loss into a machine that can be operated. “What is your vigil actually for?”

Lark answers before I can. “It’s for the living,” they say simply.

Rowan’s eyes flash. “I didn’t come here for—”

“You did,” Lark says, and the words land like a bell. “You came here because the world made you illegible in its records, and you want the sky to write what the regime erased. You came here to make absence visible. That’s living work.”

Rowan’s hands tremble. “And if he’s dead?” they whisper, and the question is a knife.

Lark’s gaze doesn’t soften, but it deepens. “Then the mark will not raise him,” they say. “But it might keep you from becoming dead while you wait.”

Rowan looks away, jaw clenched. Their shoulders shake once. Then they straighten. “No,” they say, voice ragged. “No. I’m not here to be comforted. I’m here to be answered.”

Answered.

The radio crackles, as if offended.

My misbelief flares — precision prevents loss — and I cling to it because it’s the only thing between me and the old minute.

“Two more glove changes,” I say abruptly, returning to procedure like a drowning person returning to air. “Then we resume. I’ll check your wrap. Then we’ll keep going until alignment. And at alignment I’ll ask again. Consent. Always.”

Rowan nods stiffly. “Okay,” they say, and their voice is a thin bridge.

The clock reads 01:57. Twenty minutes to the circled minute. My heart pounds as if it can outrun it.

The Word in Skin

Back at the chair, I unwrap Rowan’s side and the constellation stares back at me: lines like sutures, dots like punctures of sky, the missing star now hovering so close to the heart-line it feels indecent.

“Okay?” I ask Rowan.

“Yes,” they say.

“Want to stop?”

“No.”

I re-ink the caps. I swap to a fresh cartridge — fine liner, sterile, sealed. I stretch Rowan’s skin and place the needle tip at the next dot. The machine hum resumes its chant.

Outside, faint through the sealed windows, there is a sound like soft sand against glass: the meteor shower starting, the sky shedding itself in silence.

Inside, the sterile light is relentless. It makes everything look like an operating theater. It makes every drop of ink look like a decision.

The radio’s static thickens as 02:10 approaches. Lark adjusts the antenna, then stops touching it, hands folded as if in prayer they would deny.

Rowan’s breathing grows shallow. Their knuckles go white on the chair arm. “It’s coming,” they whisper.

“We’re on track,” I say, and the phrase feels obscene.

At 02:14, the overhead lights flicker again, longer this time. The machine hum wavers, then steadies. The radio spits a burst of noise so sharp it sounds like a consonant.

Rowan gasps. “Did you hear—?”

“I heard static,” I say, too quickly. The denial is brittle. The air feels charged. My skin prickles under my sleeves.

At 02:16, one minute before the circled minute, the dot moves again.

Not a millimeter. Not a slow drift. A jump.

It appears now directly on the heart-line, right where the stencil’s geometry would never place it. The dot is darker, more saturated, as if it has fed on attention. It is a period at the end of a sentence I haven’t read yet.

Rowan sees it in the mirror and makes a sound that is half prayer, half gasp. “Yes,” they whisper. “Yes—”

My hand freezes. The needle hums above skin. My throat tightens so hard it hurts.

This is the hinge. This is the room tilting. This is the point where my misbelief either holds or breaks.

“I can’t tattoo a moving stencil,” I say, and my voice shakes despite all my training. “It’s not safe. It’s not—”

Rowan’s eyes lock onto mine in the mirror. “You can,” they say. “You’re just afraid you’ll miss it.”

The sentence hits me with surgical accuracy, and my body answers with another spiral-memory, one sentence that is also a wound:

02:17: my hand on the door handle, the hum of the machine still in my ears, the chair empty when I come back.

My breath stops. For one heartbeat I am in two rooms: this sterile chapel, and the other locked room I failed by leaving.

The radio’s static rises, loud, then drops into a thin trembling tone like a single note held too long.

Lark stands up from the counter. They move toward the chair, slow. “Ash,” they say, and my name in their mouth is a steadiness. “Ask. Again.”

Consent. Anchor.

I look at Rowan. My voice comes out hoarse. “This is the alignment minute,” I say, and the words taste like rust. “The stencil is changing. I need your consent to continue under these conditions. Pain may increase. We can stop now. We can wait. We can—”

Rowan doesn’t let me finish. “Yes,” they say. Then, softer, almost unbearably, “Please. Don’t leave.”

The last phrase is not about the tattoo. It is about something older. It is about the threshold. It is about Gethsemane. It is about my own failure, named without being named.

I feel something in me try to reach for protocol like a weapon: Reprint. Reset. Calibrate. Control. I glance toward the printer in the back room as if it could save me.

The printer, as if hearing my thought, spits out a strip of paper by itself.

Whir. Heat. Curl.

The receipt printer at the aftercare counter — unprompted — prints a line of text, black on white, and the paper snakes out like a tongue.

I don’t go to it. I don’t let myself step away.

I stay.

The act of staying is not heroic. It is not clean. It is a shaking, ugly obedience to something that isn’t mine.

My hand lowers. The needle meets skin.

The moment the needle punctures at the new dot, the ink behaves wrong.

Instead of sinking obediently into dermis, it blooms. A comet-like bleed — thin tail, luminous head — spreading a fraction beyond where my hand placed it, as if the skin is receiving not pigment but signal. The glow in the ink vial on the counter intensifies, responding like a living thing.

Rowan sucks in a breath so sharp it’s almost a cry. Their fingers dig into the chair arm. Tears spill from the corners of their eyes, not from pain alone. Something else. Recognition. Contact.

The radio’s static surges into a pattern — not words, not music, but rhythm. It sounds, absurdly, like someone trying to speak through a mouth full of water.

I keep tattooing because stopping would be an attempt at control, and control is the false god that has already cost me.

Dot. Line. Wipe.

Dot. Line. Wipe.

As I follow the stencil, the constellation-lines begin to do something they weren’t doing before: they curve. They shift. They make a shape that is not astronomical.

In the mirror, over Rowan’s ribs, a cluster of dots and lines resolves into letters — not sharp, not printed, but legible in the way wounds are legible when you stop lying about them.

A fragment. A name. A command.

STAY.

The word is not in the ephemeris. The word is not in the software. The word is not in Rowan’s paperwork. It is in my body-memory, written in the minute I fled and something happened without me.

My stomach drops. My hands go cold. The room goes too bright. I want to laugh. I want to vomit. I want to rip my gloves off and run.

Instead, the only thing I can do is continue to ink the letters my hand is being asked to trace.

This is the intolerable: not that the sky has a message, but that the message is for me, carved into someone else’s flesh like a mirror I cannot look away from.

Rowan sees it too. Their eyes widen in the mirror, and their mouth opens on a sound that might be “Elias,” might be “Amen,” might be my name. They press their forehead to the chair’s headrest as if bowing.

“It’s—” Rowan whispers, voice breaking. “It’s telling—”

“It’s telling me,” I think, but I don’t say it. Professional talk around aftercare. Keep the silence. Don’t steal their grief to feed my guilt.

Lark’s voice comes from behind me, low as a benediction. “Keep watch,” they say.

The hum of the machine is louder now, not because I increased voltage but because my attention has widened enough to hear what was always there: the chant inside the metal, the prayer inside the procedure, the way a needle’s repetition can become litany if you stop pretending you are only doing work.

I finish the last line. I wipe the skin clean. The constellation — now also a word — glows faintly under the overhead light, a stigmata-map, a ledger, a wound that is also a guide.

The radio tone collapses back into static. The power flicker stops. The room exhales as if it has been holding its own breath.

Rowan is crying silently. Their shoulders shake. They do not speak. They do not thank me. They do not ask if it means Elias is alive. They simply sit in the chair and let the mark exist.

My hands hover above their skin, gloved, stained with ink and antiseptic.

The veil drops — not answers, but recognition: I am seen. I am named. I cannot hide behind precision. The cosmos does not merely loom. It addresses.

And the address is not condemnation. It is mercy with teeth.

STAY, it says. Not as surveillance. Not as a chain. As a command that is also a rescue.

Stay in the room. Stay in the minute. Stay with the wound long enough for it to become something other than a trap.

I take a breath. It hurts. I take another. It hurts less.

Rowan whispers, almost inaudible, “Thank you,” and I don’t know if they are thanking me, or Elias, or the sky, or the act of being told to remain alive.

“I’m here,” I say, and for once the phrase is not professional.

Morning Leaves a Trace

Dawn arrives like bleach. It doesn’t spill in; it erases. The neon outside turns pale. The street’s wet shine becomes ordinary. The meteor shower is over, leaving no ash, no proof.

Inside, the shop looks exactly like what it is: a clean room with machines and paper and biohazard bins. The sacredness drains back into objects. The terror softens into residue.

Rowan stands at the aftercare counter, shirt half-buttoned, posture careful around their fresh tattoo. The constellation on their ribs is wrapped in a clear second skin that catches the morning light and holds it. Underneath, the ink’s faint bioluminescence is visible if you look without pretending not to.

The missing star is no longer missing. It sits on the heart-line like a period that has decided to remain.

Lark prints the aftercare sheet from the receipt printer. The little machine whirs, heat head burning words into paper the way a needle burned dots into skin. The strip curls out. Lark tears it off and hands it to me.

“Read it,” they say.

My throat tightens. My hands, still gloved, take the paper. The instructions are standard. Clinical. Imperative. And because I am exhausted and raw and still inside the echo of the word on Rowan’s ribs, the imperatives read like liturgy.

Rowan watches my face as I read, as if the paper might speak again.

I clear my throat and begin, voice steady, professional — until it isn’t.

AFTERCARE — VIGIL WORK

- KEEP COVERED for 2–4 hours. Do not expose the fresh mark to unclean air.

- WASH HANDS before touching the area. Sterility is not purity. It is care.

- GENTLY CLEAN with fragrance-free soap and lukewarm water. Do not scrub. Do not punish. Let what is there be there.

- PAT DRY with a clean paper towel. Do not rub. Do not erase.

- APPLY A THIN LAYER of recommended ointment. Enough to keep the skin from cracking. Not enough to smother it.

- DO NOT PICK scabs or peeling skin. Healing will itch. Healing will lie to you. Do not answer with violence.

- AVOID SUBMERSION (baths, pools, bodies of water) for 2 weeks. Let the wound close before you return to depth.

- AVOID DIRECT SUN until fully healed. Light is a gift. Light is also exposure. Choose your timing.

- MONITOR FOR SIGNS OF INFECTION (excess redness, swelling, heat, discharge, fever). If the body warns, listen. Seek medical care.

- RETURN FOR A CHECK in 7–10 days. Do not carry it alone if you don’t have to.

At the bottom, there’s a blank line for artist notes. Lark’s handwriting is usually there — tight, controlled, nothing wasted. Today the line is empty.

Lark looks at me. “Add what you need,” they say, and their calm is the last push. “Last line is yours.”

Rowan’s eyes flick to my hands, then back to my face. Their consent has been intact all night. Their grief has not diminished. Their brother is still missing. The regime is still out there. The sky has not become benevolent.

But something has shifted. Not solved. Shifted.

I take the pen.

My hand shakes once.

Then I write, small and clean, on the blank line:

If the minute returns, do not leave the room. Stay.

I tear off my gloves and drop them in the biohazard bin, the snap of latex like a small ending.

Rowan reads the line. Their throat works. They nod once, as if receiving a benediction they did not know they needed. They fold the paper carefully, reverently, and tuck it into their pocket like a relic.

Outside, dawn keeps bleaching the world into legibility.

Inside, I look back at the ephemeris pages on the counter — at the hard red circle around 02:17 — and I finally understand what the circle was never for: not to trap the minute, not to prevent loss, not to surveil the sky into obedience, but to mark the place where I am asked, again and again, to keep watch.

Not for proof.

For presence.