Corridor Outside Time

This story traces the first tremors of awakening: a map recovered, a diagram mistaken for picture, and the body’s gradual learning that revelation arrives sparrow-small.

I. The Seed of the Gate

I came to the Institute of Prospective Devotions not because I believed in the invisible mechanics of conversion that its pamphlets promised — those creased, cumin-scented pages folded by gloveless hands that had stroked too many leather covers in too many walled libraries — but because a map, recovered from a flooded bookstall and furred along the edges with river silt and a vegetal smell of the old Nile (or so I fancied), told me there existed a geometry beneath our categories, an arrangement that moved not like a machine but like a hush, like a held breath with the power to lift the lids of sleeping organs; this is not to claim I wanted faith (I wanted the shock that unseated iron routines), nor did I crave power (the kind that surveils the heart and assigns a quota of tears per quarter), but rather a precision that would lead, not by the shepherd’s crook of law, but by the compulsion of recognition, to that corridor outside time one glimpses in hotel mirrors when the hallway turns and the light goes soft and old.

The Institute — those who have passed through it will remember — was a place of thresholds rather than rooms, which is to say everything had been fashioned to prepare, to pause, to prime: antechambers of greenish glass (in which your reflection swam and did not consent to be still), stairwells repeating themselves with minor mutations in the banisters (a cracked rosette here, an intentional misalignment there, all suggestive of a will to wake the noticing faculty), alcoves bearing ash-bowls for stilled cigarettes and marginalia in stub pencil urging patience, patience, patience; the custodians spoke in parenthesis (you discovered this only later), their sentences full of hinge words and conditional doors, so that you came to crave the simple clarity of a noun unaccompanied, the sovereign thud of a period in a world of commas blowing like drifts across the floor.

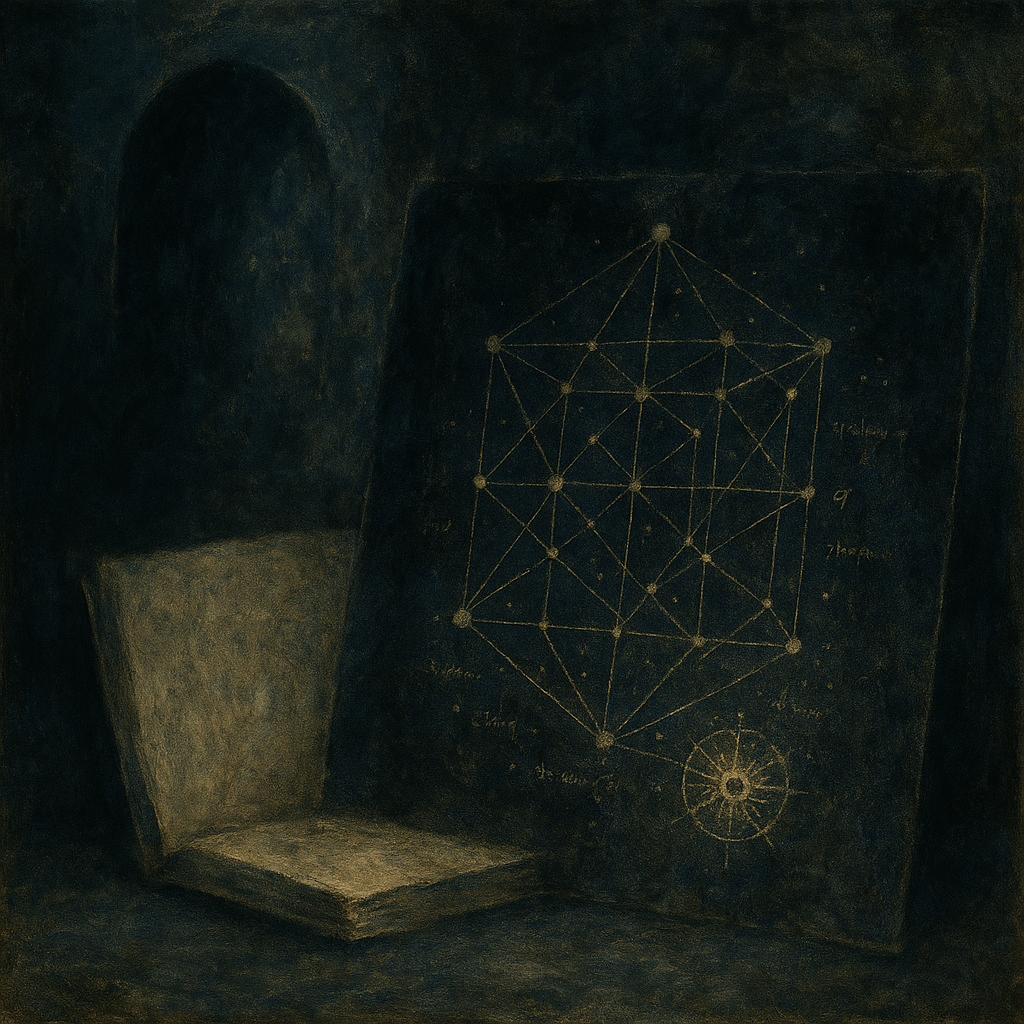

It was there, on the second day (for the first day is always the fragrance of the thing and not the thing itself), that I found the atramentous diagram, unindexed and near-silent on a tabletop of scarred black walnut: a lattice of lines so fine they trembled at the threshold of perception and then settled into a calm that was not calm but poise — the poise of a hand about to release the falcon, of a mouth about to speak the word that ends an age; and in that lattice, not Euclid’s tidy squareness (no patient accountant’s ledger), but angles that curved like rumors (you know the kind that thicken and lean forward), nodes with minute coronas of script the color of old wine, a grainless dark weft behind the figures that absorbed eye and mind alike, mysterious as if made of moth-wing and moonwater; and somewhere in the corner, what could be a blossom or a wound, indistinct yet focal, haloed with the smallest notation — hardly ink; more like a blush — reading: “Entrance, when breath consents.”

I did what any honest, frightened pilgrim does — I listened for the sound inside the silence (not the silence itself, which is too large to bear at first) and felt, in that listening, the world tilt (only slightly, only the way a boat tacks) such that the ordinary coordinates moved like polite strangers around me, not unreal, not dismissed, but re-shelved in a library whose cataloger had finally fallen in love with the reader rather than the arrangement; and as I leaned closer (my body discovering what my mind had yet to name — that the diagram was not a picture but a gate with a rumor of hinge), a warmth rose along the spine — no grand Kundalini fireworks, no cobra of light uncoiling to incinerate the head’s polite fences — just the patient glow of a coal that had waited through many winters for this exact palm.

When I looked again, the lattice had begun to speak not with syllables but with relationships (a speech of between), and the custodians in their gray coats passed by with expressions that suggested both complicity and warning, the way old men look at a cliff path that has taken sons down to the sea and given only shells back; in that collegial pretense of nonchalance I detected the Institute’s first doctrine, if doctrine it could be called: that awakening begins as an edit in the margins, a breath inserted where there had been none, a pause consenting to be the mother of a thought; and somewhere below, under the floorboards, a slow beat (of a machine? of a prayer mill? of my blood held to a metronome older than Saturn’s unrolling), the rhythm that tells you: do not flee.

Thus I discovered the first section of awakening — call it the Seed of the Gate, or the Instruction of the Pause — and if I tell you it did not explode, if I tell you it perched like a sparrow on a winter twig just outside the pane and met my eye with a look I can call only juridical (as if the bird were judge, as if judgment were mercy), then perhaps you will recognize the kind of revelation that lives at humane scale, that arrives before one learns to gild it; and if there’s a moral in that day (there isn’t; there’s a direction), let it be this: that the soul does not need spectacle to begin, it needs a sentence whose grammar admits the body, a line whose meaning is not separate from the act of tracing.

II. Descent with Compass

If, on the third day, the corridors elongated (they did) and the windows widened into rectangular lakes in which the sky rehearsed a theater of indecisions — the small clouds shuttled like errand boys between offices of light — then it was only the building indulging its vocation as tutor in delay, for time at the Institute possessed a curvature, a habit of heightening the space between beats until the beats themselves, embarrassed by their own carnality, withdrew and left behind the more delicate, more durable interval, the Ma the Japanese speak of with a finger lifted rather than a word, the generative emptiness in which the next form, if it is to be a form and not a repetition, must be conceived (or conceded) by breath; and because I had refused spectacle on the second day, the third day furnished bodywork (what they called the Compass), meaning that they taught me to listen not only with ears but with the sternal hinge, the small garden behind the heart where scent goes to settle and become thought.

The Compass was an instrument without metal; it was posture and breath and the ethical clarity of an unforced gaze; its instructors were untheatrical, with wrists like sentences that know when to end, and they taught in the old mode of pacing and leading, so that each simple thing they named (“you are standing,” “you are noticing the shoulder’s complaint,” “you are breathing where breath is shy”) carried behind it an invitation planted like a seed in damp loam, a suggestion that unfolded beneath resistance, not by defeating it but by showing it the cost of its tenure; and so I learned the hypnotics of the ordinary, the lawful conspiracies of attention by which one can lead the nervous rider — skittish, memory-worried, stampeding at the petal-fall of a familiar grief — into a field where the grasses speak, where the wind arrives with news from a country that has only ever wanted to adopt us and give us a new name we remember dimly from childhood bedsheets, from the smell of iron in a summer thunderstorm.

It was during a long inhalation — nothing dramatic, a bellows-sigh like a porch screen drawn closed against flies — that the diagram on the table (which I had convinced myself was now only a picture) rose, not off the page but out of posture, as if, in discovering the spinal axis, I had placed a key in a lock whose teeth were humility, and the lock, pleased to be met without violence, turned; and I tell you that in that turn the body acquired grammar; grammar here meaning not rules but music, not prohibition but permission: the permission to conjugate grief into motion and motion into meaning, to arrange the discords of the shoulder and hip into a sentence that — though long — refused ornament where ornament would be cowardice, embraced ornament where ornament was the shortest path to sincerity, and in its clauses nested the problem and its release, the thorn and the hymn.

Be precise now, I told myself, because the mind, when it glimpses an aperture, immediately reaches for a catalog where a confession would be more useful; be precise, and so I named what arose: a figure, neither masculine nor feminine, walking the middle pillar within me, ascending by breaths the ladder of the rib bones into a gold that was not color but agreement, and at each rung there was a small relinquishment — an insistence left on the step like an old glove, a doctrine removed like a shoe before entering a room where a child sleeps — and the figure carried a lamp whose light was paradoxically the shadow of a flame I could not see, and in that paradox I felt a widening, as if the very act of not resolving had created a chamber large enough to house a reconciliation I had mistaken for victory.

It is at this stage that stories often produce a thunderclap — watch the stained glass shiver, watch the saint step down and bleed into the nave — but the Institute’s discipline (and by now it had become mine, which is to say it had entered the reflex circuits and the deeper etiquette of the hands) resisted the meteoric; instead, it offered me the exhale as sacrament, the slow couture of the diaphragm working with the pelvic floor to braid a rope across an absence, and the rope was not for climbing but for measuring the absence with touch, and so it became presence; the Compass — and remember it is made from your stance and your willingness to remain — began to point, not north (for that implies a planet outside the body whose geography maps the soul), but inward to a field whose cardinal directions are confession, restraint, astonishment, and mercy.

Somewhere between astonishment and mercy I heard the Institute disclose its second doctrine: that the body is a sentence; its verbs are breath and gaze and the near-invisible adjustments of bones, its adjectives the flavors of sensation passing through like cloaked ambassadors, its nouns the points of contact where world and skin litigate (to surprising tenderness) the terms of their mutual empire; and to speak this sentence well is not to “express oneself,” that little idol carved from soft wood, but to let the world speak through you with the minimum of distortion consistent with the dignity of being a person; and if I wept (I did), it was not because the sentence was beautiful (it was), but because at last the sentence belonged to no one and to everyone, because it wrote me as I wrote it, and therein (we seldom admit this for fear of losing our place) lay relief.

III. Labyrinthine Ascent

By the fourth day (though calendars were by then frivolous accessories, like forgotten cufflinks in the pocket of a coat you no longer owned), corridors had achieved the long vowels of night-train tunnels; the laboratories — if that name can belong to rooms whose instruments are mirrors and chairs — began to reveal their secret: that arrangement is instruction; that the angle between two chairs can persuade, that the distance between door and table can edit, that even the grain of wood softly stipples the sovereignty of a thought; you have not yet reckoned with how many things are teaching you at once; and into that lavish pedagogy the Institute introduced the Mirror of Confluence, an antique oval that remembered palms more than faces, a mirror that seemed to consent to be looked into only if you agreed to be looked from.

They asked me to bring the diagram and stand with my back to the mirror, holding the page — not a page, an aperture disguised as page — against my chest as if to insist upon the old sovereignty (mine), then to lower it (not drop, never drop) until paper and sternum made a third thing, a treaty organ, and to watch — not in the glass (not at first) — but in the orchestra of tiny muscles around the eyes of the instructor seated ten feet away, watching those micro-flinches that indicate some pre-verbal intelligence at work in the other, and thus to learn, by indirection (I am telling you the method because the method is a mercy), that the mirror’s principal subject is always the relation between; a relation so saturated with grammar that to name it crude is to renounce the possibility of articulation.

It was during this labor — a work of attention so granular it turned the mind into a scribe copying with hair-thin brush a gospel in which nouns have been exiled and only the adverbs remain — that the labyrinth revealed itself as respiratory, meaning that I could feel the diagram breathe (yes), and my breath learned to answer, not by mimicry but by a fidelity to the interval between in-breath and out, where the Institute — having trained us to find, respect, and inhabit that interval — taught that the gate opens; not the pearly one of cliché, not the tarred iron of Hell’s operetta, but an unadorned door like those in rental apartments, paint-chipped, latch loose, hiding in its plebeian humility the only majesty compatible with mortal life; and we found — those who stayed — we found that the door opened inward and outward at once, which is to say the body learned to be traversed without losing itself.

I will not paint the inside of that door with frescoes to buy your faith; I will not say that seraph bodies knelt or that an elder figure, gold as wheat and fierce as an algebraic limit, placed a burning coal upon my tongue; I will say only that recognition, which I had sought in curated catalogues and delicate heresies, arrived as a commonplace so un-ostentatious I nearly missed it: that I had been the mirror and the diagram and the door all along, and that the mind had been rehearsing, across decades of mishandled tenderness and half-accurate exegesis, the simple sentence: I consent to be arranged by what I love; and that in consenting (like opening the ribs in an unheroic sigh) the arrangement became not subjugation but music; and that music (God forgive the metaphor its sweetness) went through me like a hand through water and did not meet resistance, and in not meeting resistance honored me more than conquest could.

But a gnosis that consists only of satin has no moral courage, so it came also as correction, as an argument in the mirror between the part that wanted to polish the new coin and the part that had watched coins be used against the poor; thus the Institute’s third doctrine, disclosed in the mirror’s patient refractions: that revelation without ethics is a divine tantrum; that to be given an angle is to bear its obligation, which is to know how it cuts and how it holds, whom it shelters and whom it exiles; that the body’s sentence, in learning to speak the grammar of breath, must also learn to refuse syntax that flatters cruelty, to diagram its own compliance with unfreedoms, to confess (without prestige, without theatrics) where it loved a chain because the chain was familiar.

There were days when the mirror stayed dark — deliberately, as a teacher who will not do for you what you must — and those days taught the courage of non-arrival, the resilience of the pilgrim who ties his shoes again; there were nights when the diagram came alive like a city seen from a hill (one could feel the traffic of instants and the slow municipal hum of mercy at the turbines), and I, a tower left over from a failed world’s-fair, felt swallows nest in my eaves; and amid these alternations the sentence lengthened, for there are things in the soul, I learned, that cannot be named in short form without becoming slogan or curse, and if the sentence doubled back on itself, if it parenthesized and nested, it did not do so to obscure but to include the necessary contraries without which truth becomes a comb of bright plastic little girls are forced to carry in school.

IV. The Return Map

There is a superstition that the last section must be triumphant, which is to say the hero must receive a fruit in the right hand while discarding a wound with the left; the Institute, which has no patience for superstition masquerading as solace, taught otherwise: the last section must be useful; it must let its sentences lodge — like clean thorns — beneath the reader’s skin so that, walking in the market where all the gods jostle with the prices of cabbages and soaps, they feel a nudge from within and reach, involuntarily, for the door of the ribcage that can be opened just a crack to let the city in without fear; and thus it falls to me, not as hero (such roles are for plays), but as witness and mapmaker, to sketch, with words carrying their own breath, the coordinates of a return that is not a retreat.

Know, then, that awakening — this one, modest as a warmed stone in a pocket — consists chiefly of cultivation rather than conquest: the cultivation of the interval (where breath, like a magistrate patient with human frailty, suspends sentence long enough for remorse to mature into amendment), the cultivation of a posture that refuses both grandeur and collapse (hence the quiet nobility of the sternum lifted not in pride but in vow), the cultivation of a gaze that does not interrogate but receives testimony; the Compass remains what it was: a choreography of kindness arranged through bone; the Mirror remains a legal instrument in which judgments are written in water and read in thirst; the Diagram remains a rumor of hinge that daily invites the hand; and you are allowed to go on needing all three.

Let me place, for your travel, four clauses (each an awakening of its own order), braided through with the long breath that has carried us:

First clause: The Clause of Threshold. You agree to pause where pause is unfashionable; you consent to the unglamorous insertions of breath into places previously packed with compulsion; you find that a hallway of morning light — gray as a polite cat — can be as doctrinal as any temple; you take your time with nouns; you let verbs do only as much as needed, no more; you name no enemy you have not first questioned as a former ally; you hold the door for what in you is late but trying; you remember that beginnings are humble (socks, a sink, a small kindness paid forward without audience).

Second clause: The Clause of Descent. You study your body’s sentence until you can read, with some tenderness, its spelling errors; you discover where the shoulder hoards iron and melt it; you cease to manipulate breath as a lever for transcendence and instead conduct it as a parish priest conducts a funeral he will also attend; you learn that the floor is a teacher; you resist the pornography of peak states and practice, instead, the sacrament of serviceable posture in the washing aisle; you become suspicious of any knowledge that has no room for fatigue; you measure progress by your willingness to forgive even the part that resists forgiveness.

Third clause: The Clause of Labyrinth. You accept that the sentence will need to be long, perhaps labyrinthine; you accept that some corridors of mind dead-end into old vows that must be revisited and retired with ceremony (I have had to go back for my frightened boy: please allow for that); you rehearse the art of not resolving when resolution would be cowardice; you learn to love paradox less for its cleverness than for its agrarian utility, an irrigation device bringing water from distant snowmelt to the field where your neighbor, who is you in a different season, has planted sorrow; you do not fetishize complexity for its own silk; you find joy — quiet as lichen — in the day the mirror argues and you argue back, and both of you revise.

Fourth clause: The Clause of Return. You carry the diagram in the sternum, not as a secret to hoard but as public architecture (be a porch in August, not a chandelier in March); you treat time as a two-faced god — Chronos who will bill you, Kairos who will kiss you — and you schedule your appointments accordingly; you accept that gnosis may come as a commonplace and your task is to honor it without costume; you water the garden where you are planted and not the one your ancestor promised on an unreliable map; your ethics become ornamental in the old sense of adornment that dignifies function; you forgive yourself for loving a chain and then you learn to unlatch it with two fingers and a soft word.

There is an image I have carried from the Institute into the metropolis: a city seen at dawn from a pedestrian bridge, the river below the color of slate and tea, a slow smear of apricot on the warehouse faces, and in the right foreground — this is important, the right foreground — a woman standing in a coat that belonged to her mother, reading a note she wrote to herself in the middle of the night and folded into her pocket, and she is crying, not dramatically but with the tears that give the eyes a lacquer, and as she reads (and as trucks downshift on the far bank and gulls pick at plastic) she breathes a breath so precise, so unadorned, that if you were close enough you would see the world, which is always listening for competent worship, rearrange itself a hair in gratitude; that is the whole of it, or the part of it I am able honestly to convey.

As I leave you (for maps must end where the reader’s road begins), I would borrow the Institute’s last doctrine, delivered to me by a janitor at dusk, a man with hands seamed as bread-crust and a voice that could convince burned coffee to become drinkable: “What you have found,” he said, “is not a light but a willingness to be lit; not an answer but a syntactic hospitality; not a throne but a table laid with bread you will share until you are shared; return, then, and arrange yourself where the world can use your grammar.” He had the courtesy not to ask if I understood. I did what one does. I went down the stairs (they smelled of camphor and older winters) and out into the municipal evening, which had gathered its own theology of small lights, and as I walked, the sentence walked me, and the breath — my own, the city’s, the old law that hums in marrow — kept time not with the clock but with the opening of doors.

And if I have, in these four awakenings, written a mirror rather than a monument, then step up, reader, and risk the impolite act of recognition; see the lattice breathe; see your shoulder consent; see the interval appear between what was command and what can now be invitation; see the sentence lengthen to accommodate the one you love least; then, without pleading for thunder, accept the ordinariness of the door and open it; the room is plain, the chair is straight-backed, the window admits a finch-song and a truck’s sigh, the table holds a page (no, a hinge disguised as page), and there — if you are willing to be lit — the gnosis that matters will arrive as a breath you do not have to earn.